I hate polystyrene…

You’re welcome to copy the following clause into your own building contract:

Special Condition – Polystyrene Restriction

The use of polystyrene materials for construction or packaging on-site is generally prohibited. Exceptions may be made for items that arrive with polystyrene packaging. In such exceptional cases, the Builder is responsible for immediately collecting and containing all polystyrene, including any fragmented or loose particles, in a sealed container or bag designated specifically for polystyrene waste. This container must be situated away from other waste bins to prevent cross-contamination. The Builder must then arrange for the disposal of the contained polystyrene at a specified polystyrene recycling facility, such as Randwick Recycling Centre, which allows for the disposal of up to 3m³, or any other approved polystyrene recycling centres/companies.

Now We're Cooking with Electromagnetism: The Case for Switching to an Induction Cooktop

Humans have a primal connection with fire, so it's understandable that people might have some reservations about moving away from cooking over an open flame; a human tradition over a million years in the making. But there's something else that is as synonymous with humankind as making fire and that’s tools and technology. Our bodies are arguably the least furnished in the animal kingdom - we survive because of our minds, and it's our minds that enable us to create what other animals cannot, so fear not the cooktop revolution! While many still swear by their gas cooktop, the reality is that induction cooking is superior, but it's actually not anything new...

Source: KitchenAid

Humans have a primal connection with fire, so it's understandable that people might have some reservations about moving away from cooking over an open flame; a human tradition over a million years in the making. But there's something else that is as synonymous with humankind as making fire and that’s tools and technology. Our bodies are arguably the least furnished in the animal kingdom - we survive because of our minds, and it's our minds that enable us to create what other animals cannot, so fear not the cooktop revolution! While many still swear by their gas cooktop, the reality is that induction cooking is superior, but it's actually not anything new...

History of Induction Cooking

First patented in the early 1900s, induction made its debut at the World’s Fair in 1933. Frigidaire brought it to market in the 1950s and Westinghouse did the same in the 1970s, but priced at more than $11,000 in today’s money, failure was probably inevitable.

Cool Top 2 (CT2) by Westinghouse 1972

An early induction cooker patent from 1909

Over time, the technology gained popularity in Europe and Asia, where small kitchens and energy saving concepts were more widespread than in the United States or Australia. With greater availability came cost savings and with a growing focus on sustainability plus its appeal among professional chefs, the uptake of induction and the availability of different brands and product range has been steadily increasing.

How Does Induction Work?

The speedy performance of induction cooktops can seem like magic, particularly if you're used to the slow response of electric element cooktops. But it all comes down to science.

At first glance, induction cooktops look a lot like traditional electric cooktops. But under the hood they’re quite different. While traditional electric cooktops rely on the slow process of conducting heat from a coil to the cookware, induction cooktops employ copper coils under the ceramic to create a magnetic field that sends pulses into the cookware.

They work by producing an oscillating magnetic field. Because the magnetic field is constantly changing, it induces a matching flux into any magnetic cookware on the cooktop. This induces very high currents in the cookware, causing the cookware to get hot due to the metal’s electrical resistance.

Because the pot is heated directly by the magnetic field, the amount of power being fed to the pot, and hence the running temperature of the pot, can be varied almost instantly, giving induction cooktops heat control capabilities as good as or better than gas.

Source: ScienceABC

Better Than Gas?

One of the many benefits of cooking with induction is efficiency, in both terms of energy efficiency and also reduced cooking times. Traditional cooktops, both gas and electric lose a lot of their heat to heating up the room and the cooktop surface, in fact gas cooktops lose about 60% of their heat on average meaning only 40% actually goes into cooking. Induction on the other hand is around 84% efficient, meaning only 16% of the energy is lost [1]. One of the most cited examples about the speed of induction is boiling a pot of water. On a new induction cooking surface, you can boil water in about two minutes or less as opposed to 5-8 minutes on a traditional cooking surface.

Safety is another reason for induction’s rising popularity. Since the technology uses no flame, the risk of kitchen fires is dramatically reduced. It also only heats the cookware, resulting in fewer burns. Heat will still transfer from the cookware back to the cooktop surface, meaning it can still be warm, or even hot, to the touch, so don't go throwing your hand down on the surface to demonstrate that it's just the cookware that heats up!

You may need some time to get used to the difference in cooking with induction. As mentioned, one of the biggest advantages of induction is how quickly it heats up, but this means that without the build up, cues you may be used to – the slow increase in bubbles, for example, when boiling – you may get a few boil-overs to begin with. Similarly, you may find yourself needing to use a slightly lower heat than called for in a recipe. And if you’re used to having to fiddle with other cooktops to keep a constant heat level, you may be surprised by how well induction can maintain a steady simmer.

Cleaning induction cooktops can be easier because there are no removable grates or burners to get under or around to scrub, and food is less likely to scorch and burn given the reduced surface temperature of the cooktop, you can even cook with silicone mats under the cookware.

Finally, don't be fooled by the best marketing campaign the gas industry ever ran. "Natural" gas is a harmful fossil fuel. It’s mostly made up of methane, the second most significant greenhouse gas after carbon dioxide. When you're cooking with gas you’re getting a regular dose of air pollutants quite close to your face. Burning methane forms nitrogen dioxide (NO2), carbon monoxide, nitrous oxides and formaldehyde. NO2 is problematic because it can cause a range of very serious health problems, including asthma. Research in both the US and Australia indicate that one in eight current childhood asthma cases can be attributed to gas cooktop emissions. With an estimated one in 10 Australian children affected by asthma, this is cause for concern [2].

Dispelling The Myths

1. Wok Cooking

Dedicated wok cookers have been known to say they’d never go induction. However, induction and woks go together quite well, you just need a flat bottomed wok! Induction cooktops perform really well with stir fry cooking because they heat up quickly and evenly.

2. Induction Cooktops are Noisy

Well... they make noise, but are they noisy? For some context you might say that they're noisier than the hum of a quiet dishwasher but not as noisy as a microwave. An induction cooktop will make some noise during operation partly due to the fan used for cooling, and the amount of noise they make will vary depending on the quality of the appliance. Other noises such as clicking may be due to the cookware not registering properly, the cookware may not be on the zone properly, or may not be the right size for the zone, or may not be fully induction-compatible. If you’re concerned about noise, test one out at your local appliance store (they often hold cooking demonstrations) before you buy.

3. You'll Need New Cookware

The truth is that the cookware you have is probably already induction-compatible and if you're not sure, all you need to test if they are is a magnet off your fridge. If it sticks to the bottom of the pan, you’re good to go. Cast iron, enamelled cast iron, and many types of stainless steel (but not all) cookware are all induction compatible. Aluminium, copper, and glass cookware will not work. If you have an induction cooktop, but a favourite piece of cookware doesn't work on it, you can get a stainless steel adaptor that can be placed on the cooktop under the pan. If you're buying new cookware just look for the induction symbol on the packaging.

Get Off The Gas!

Gas is a fossil fuel. Installing a new gas cooktop means that appliance and your home will always rely on fossil fuel. Whilst it is a fair argument to make that if your home is connected to the electricity grid than even an induction cooktop is still powered by fossil fuels, but it's not that simple.

Nearly one out of every three Australian homes now has solar panels, and with recent increases to building code sustainability targets more renovations and new builds will need to include energy generation in order to meet these targets [3]. With the cost of batteries incrementally decreasing more homes also have the capacity to store and use the power they harvest even when the sun goes down.

But even if your home doesn't have rooftop solar that doesn't mean your home isn't being run by renewable energy. As of 2023 renewable sources contributed an estimated 95,963GWh, making up 35% of Australia’s total electricity generation (compared to 15% in 2016). South Australia leads the way with a whopping 74% of the states electricity generation coming from renewable sources [4]. Politics depending, the percentage of our electricity grid coming from renewable sources is only going to continue to increase. The point however is that gas will always be 100% a fossil fuel.

Final Thoughts

So if you're renovating or planning a new build let your electrician know that you want an induction cooktop as you may need an upgrade of your electrical switchboard or the wiring to your kitchen. Even if you don't own your own home you can still make the switch to induction with a portable benchtop induction hob.

Source: Epicurious

Many professional kitchens have switched to induction cooking in the last few years. This isn’t surprising, given that induction offers better control, speedier cooking, and reduced exposure to fumes. It’s also more energy efficient and, therefore, often cheaper.

Still on the fence? Give induction a try, many appliance showrooms hold cooking demonstrations, or find a friend who already has induction and ask if you can cook for them, I'm sure they'll oblige!

[1] https://www.leafscore.com/eco-friendly-kitchen-products/which-is-more-energy-efficient-gas-electric-or-induction/

[2] https://www.unsw.edu.au/newsroom/news/2023/02/a-heated-debate--how-safe-are-gas-stoves--

[3] https://www.solarquotes.com.au/blog/nathers-ratings-homes-mb2611/

[4] https://www.energy.gov.au/energy-data/australian-energy-statistics

Insurances During Construction

The various types of insurance relevant to a building project can cause confusion as there is no “all encompassing” insurance. Each type will cover a different thing and they are often provided by various people, sometimes the owner, sometimes the builder, or there may even be an option for either party to take out the insurance which should be clarified prior to signing a building contract to avoid disputes.

The various types of insurance relevant to a building project can cause confusion as there is no “all encompassing” insurance. Each type will cover a different thing and they are often provided by various people, sometimes the owner, sometimes the builder, or there may even be an option for either party to take out the insurance which should be clarified prior to signing a building contract to avoid disputes.

Home Building Compensation Fund

Sometimes called Home Owners Warranty, the Home Building Compensation Fund (HBCF) provides a safety net for home owners in NSW faced with incomplete and defective building work carried out by a builder or tradesperson. Home building compensation cover protects homeowners as a last resort if their builder cannot complete building work or fix defects because they have become insolvent, died, disappeared or had their licence suspended for failing to comply with a court or tribunal order to compensate a homeowner.

A HBCF policy can be provided by either the owner or the builder so it should be clarified if the builders price for the project includes or excludes HBCF.

Information about the home building compensation scheme (previously known as home warranty insurance) can be found at www.icare.nsw.gov.au/government-agencies/our-funds-and-schemes/home-building-compensation-fund

Contract Works Insurance

A builder should have contract work insurance. It is for your protection and covers the loss or damage to materials and work.

Contract works insurance, sometimes referred to as “Construction All Risks Insurance“, covers accidental risks of physical loss or physical damage to the contract works during construction. If the builder does not have this type of insurance, you may risk:

inconvenience

time delays

disputes (and possible financial loss) if materials are damaged or stolen.

Public Liability Insurance

Public liability insurance covers the builder or tradesperson if anyone is injured as a result of the building work, or for any damage caused to a neighbouring home or to third party property. If the builder or tradesperson does not have this type of insurance, you could be liable because you own the property.

While public liability may sound similar to workers compensation, the easiest way to think about the differences is simple. Workers compensation is for the builder or tradesperson and their employees. Public Liability is for any non-employee that deals with or comes in contact with the builder or tradesperson, their employees, or the building site.

Workers Compensation Insurance

Make sure all employees are covered by their employer for workers compensation. This insurance covers employees who are injured on the building site.

If employers are not insured, you could be liable to pay the costs of any claim. In some circumstances, under the Workers Compensation Act 1987, these people are regarded as your employees.

Professional Indemnity Insurance

Professional indemnity insurance (PII) covers certifiers, architects, engineers and building consultants for claims against professional services provided. Services can include advice, design, certification, contract administration and project management.

As a registered architect, Ironbark Architecture is required by the Architects Act to hold current Professional Indemnity Insurance as well as Public Liability Insurance at all times.

Other insurance issues for homeowners

If you’re renovating or extending an existing home:

notify your home insurance provider in writing before construction begins

find out if your home and contents insurance policy will cover damage or theft to your home during the period of construction; sometimes, if you don’t inform your insurance company before the work begins, you may not be covered at all

your lender (if borrowing money to fund the project) will want to see a current certificate of insurance to make sure you are protected

if the value of your home has increased as a result of renovations, you may wish to increase the value of your home/building insurance policy.

For any concerns or questions you may have regarding the various insurances related to a building project you can obtain advice from the insurance facilities offered by either the Master Builders Association (MBA Insurance Services) or the Housing Industry Association (HIA Insurance Services).

Information sourced from:

https://www.icare.nsw.gov.au/government-agencies/our-funds-and-schemes/home-building-compensation-fund

https://www.fairtrading.nsw.gov.au/housing-and-property/building-and-renovating/preparing-to-build-and-renovate/insurance

Review: Glenn Murcutt Master Class

Listening to Glenn Murcutt talk about architecture gives you a sense that this is not only somebody who understands deeply the intricacies of architectural design and construction but who also understands the landscape within which an architecture sits. A person who can look at the contours of the land and explain how they have come to be and how they influence the winds and how that might inspire a response from architecture to create a ‘sense of place’.

The Fredricks-White House turns its back to the cold winds like a man with his coat hunched up around his neck to keep out the wind. (Murcutt, 1982)

Listening to Glenn Murcutt talk about architecture gives you a sense that this is not only somebody who understands deeply the intricacies of architectural design and construction but who also understands the landscape within which a piece of architecture sits, a person who can look at the contours of the land and explain how they have come to be and how they influence the winds and how that might inspire a response from architecture to create a ‘sense of place’.

The Glenn Murcutt Masterclass has been convened annually by architect Lindsay Johnston since 2001 and brings together Glenn and fellow masters Peter Stutchbury, Richard Leplastrier and Brit Andresen each of whom are leaders in the approach of 'architecture of place' and ‘Australianness’. The course is held for the first week at one of Glenn’s few public buildings, the Arthur and Yvonne Boyd Education Centre followed by a second week in the city. It is a course that offers a rare opportunity of mentorship with outstanding Australian architects.

The Arthur & Yvonne Boyd Education Centre where the Masterclass takes place (Murcutt, Lewin & Lark, 1999)

The course was run as an intensive two week group studio, designing a building on the same property as the education centre. The course commences with a welcoming ceremony and a walk of the landscape with Glenn and Aboriginal Elder Uncle Max Dulumunmun Harrison to gain insights into 'touching this Earth lightly', an ancient aboriginal wisdom that Glenn has come to adapt to his design approach. In addition to the design project, visits are also undertaken to eight houses by Glenn, Richard and Peter. An interesting an unexpected aspect of the course is the coming together of different cultures – the course has 32 participants, of whom only a handful were Australian so there was much insight to be gained from architects from The Americas, Asia, Africa, Europe, Oceania and the Middle East.

Working through our groups design ideas with the Glenn, Peter and Brit (photo by Louise Montgomery)

In addition to the opportunity to speak one on one with the masters throughout the two weeks they each gave various talks about aspects of their work or projects where inspiration and wisdom is passed on. From the course I took away two themes in particular - Responsibility and Integrity. Responsibility was raised first by Glenn who discards the notion of sustainability, a ‘theme’ which is often treated as more of a sales pitch than anything else. Responsibility, Glenn says, encompasses sustainability but also goes beyond to include responsibility to the environment, responsibility to the clients, responsibility to the place and responsibility to the materials, right down to the way that the building is put together so that at some point in the future if the building is not needed anymore it can be disassembled, recycled and reused with a minimum of fuss. The second theme was integrity. Integrity from the architect, integrity from the client, integrity from the builder, as well as integrity of cost, material and quality. With these themes kept in mind, architecture that improves people’s lives has the opportunity to be created, making places of sanctuary, made from the heart.

Simpson-Lee House (Murcutt, 1993)

Glenn explaining the sliding door system at Simpson-Lee House (photo by Sophia van Greunen)

Sketching details of the Simpson-Lee House (photo by Jason Surkan)

Glenn imparting wisdom at Simpson-Lee House (photo by Jason Surkan)

The highlight of the masterclass was the opportunity to visit a number of projects by the masters. None of these were particularly ‘showy’ houses, made from mostly raw materials such as corrugated steel, concrete and hardwood timbers. But these are houses of divine warmth and made with such craftsmanship that some are closer to being pieces of furniture than they are houses. The owners of each warmly invited us into their homes to tell us the story of how each came into being and their experience working with the architects, each of them now appearing to be more ‘friend’ than ‘client’.

Cabbage Tree House (Stutchbury, 2017)

The masterclass ended with a barbeque at the house of Richard Leplastrier, if you can even call it such a thing - novelist Peter Carey called it an ‘extraordinary campsite’ and Glenn Murcutt once called it ‘like a Swiss watch, just an exploded one’. The house is a platform, one large room that serves most of the functions of living and a large deck that serves the others. In the centre of the deck is a timber bath tub heated by a wood fire. There is no glass in the house, just openings that can be open or closed to open the house up to the breezes, or to ‘batten down the hatches’ in the brunt of winter. It’s not the sort of house that everyone would want to live in and there would be times of discomfort that come with living like this, but what it does achieve is an exploration of the idea ‘how little do we really need?’, and if the price to pay for living with such a strong connection to the landscape, with the Pittwater as a living room, with Kookaburras as dinner guests and that timber tub for bathing is a month or so of being a bit cold… I think it’s probably something I could get used to.

Lovett Bay House (Leplastrier, 1994)

So after my two weeks with the masters I have come away invigorated. A connection between the built and natural environment is always something I try to make an important part of my designs so that the occupants aren’t locked away in their homes with the environment ‘at arm’s length’. This course has reiterated for me just how special the solution can be when an architecture is designed to have a ‘sense of place’.

Richard showing some drawing techniques (photo by Jason Surkan)

Emerging Material Use: Bamboo

Bamboo is a mystical plant: a symbol of strength, flexibility, tenacity, and endurance. Throughout Asia, for centuries bamboo has been integral to religious ceremonies, art, music, and daily life. It can be found in paper, the brush, and the inspiration for poems and paintings. It is a material that had interested me for a long time and I yearned to know more about it.

German-Chinese House, EXPO 2010 by Markus Heinsdorff

Bamboo is a mystical plant: a symbol of strength, flexibility, tenacity, and endurance. Throughout Asia, for centuries bamboo has been integral to religious ceremonies, art, music, and daily life. It can be found in paper, the brush, and the inspiration for poems and paintings. It is a material that had interested me for a long time and I yearned to know more about it.

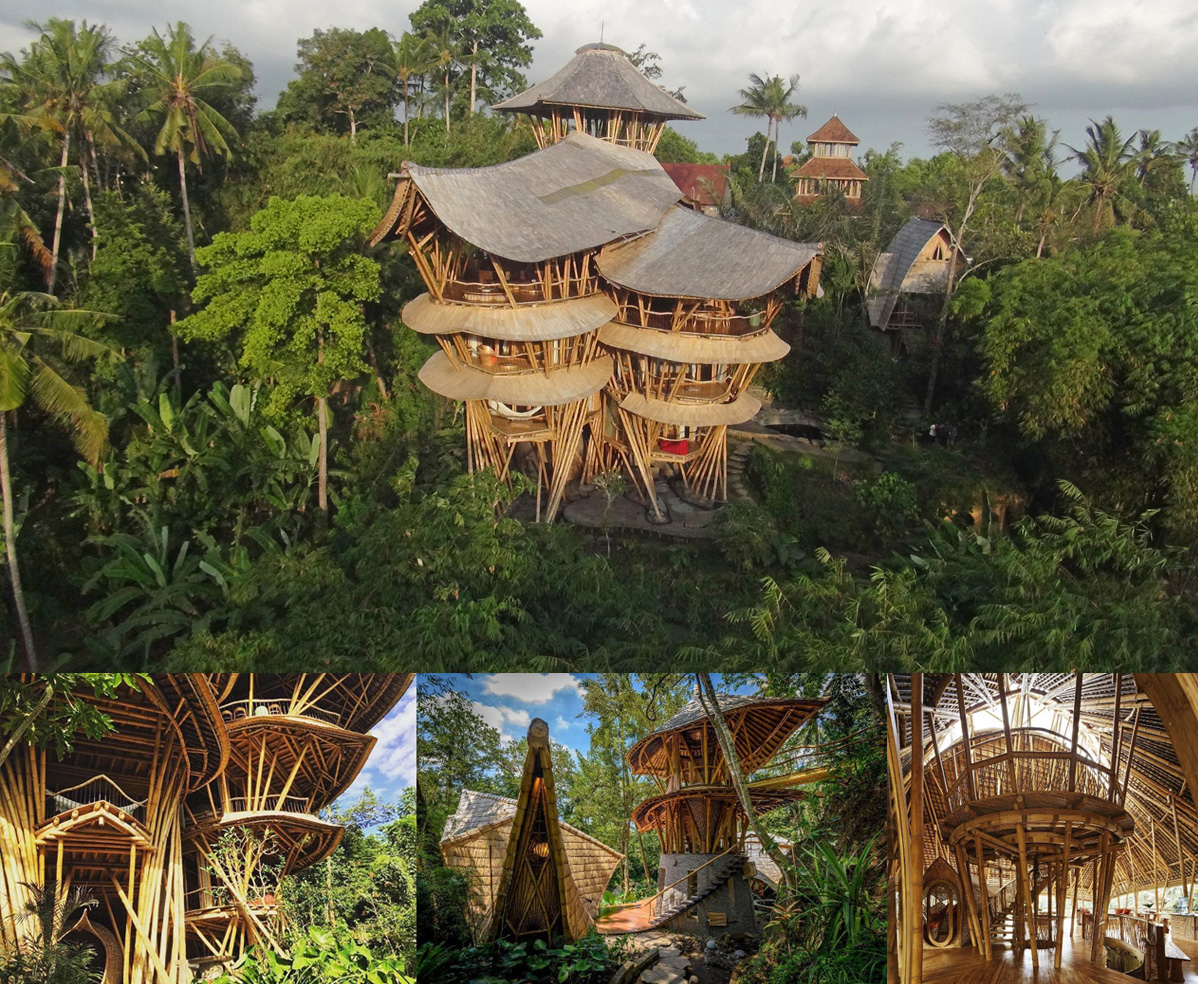

In early 2017 I undertook an immersive course just outside Ubud in Bali, Indonesia called 'Bamboo University' run in collaboration with Ibuku. Ibuku is a team of young designers, architects and engineers exploring ground-breaking ways of using bamboo to build homes, hotels, schools, and event spaces in Bali, Indonesia. As part of the course we visited a number of buildings completed by Ibuku which crush the misconceptions about the applicability or limitations of bamboo in contemporary architecture.

A selection of works by Ibuku built almost entirely from bamboo

Ibuku is spearheaded by Elora Hardy, the daughter of John Hardy, well known for his conception of The Green School in Bali which is an inspirational project bringing sustainable education to the youth that attend the school.

Green School, Bali, Indonesia

Bamboo is a highly efficient building material. The key advantages of bamboo are:

Bamboo does not need to be sawn into a profile, instead it can be used in the round. This significantly reduces the processing required.

Bamboo has a hollow core, giving it a structurally efficient cross section.

Bamboo has a strength close to concrete, and its strength-to-weight ratio is similar to steel.

Bamboo grows in 3 to 5 years compared to 30 to 50 years for most softwoods and hardwoods.

The use of bamboo has historically been limited due to decay and fire risk. However, treatments have been developed to eliminate these risks.

More than 1500 species thrive in diverse terrain on every continent but the poles. It also grows the fastest: Some species grow one and a half meters a day!

Model making of a theoretical bamboo structure

The course was an idea originally conceived to help teach professionals about the potential of bamboo as a green building material. In its current form it is a design and bamboo building workshop. We spent time visiting Ibuku creations, model making and constructing 1:1 structures from bamboo.

Learning joinery techniques from Iocal builders

The latter portion of the course was dedicated to constructing an open form structure built entirely from bamboo save for a few bolts and a metal roof. I learnt that building with bamboo requires an entire shift in perspective as few of the techniques used in conventional timber frame construction are applicable.

Whilst bamboo as a material has advantages such as its lightness, strength and flexibility it does have limitations that need to be addressed in order to achieve a prolonged lifespan. Bamboo has a low natural resistance (1 to 3 years) against attacks by fungi and insects. It is difficult to treat with normal preservative methods since its outer membrane is impermeable to liquids. At Ibuku, they treat bamboo with a natural Boron salt solution, which protects it from insect attack for a life-long period.

Bamboo is also sensitive to direct UV exposure. The surface of bamboo becomes rough under UV exposure, and the strength of exposed bamboo can reduce significantly. High energy UV radiation leads to evaporation of water under the surface, and cracks will enable water to escape from the bamboo. The UV exposure also breaches the chemical bond at the surface of bamboo.

The application of bamboo in the Australian construction market (beyond decorative applications) is fraught with obstacles at present: there is limited documentation on the structural behaviour of the material and the skills and knowledge required both for construction and certification limits opportunities. However, there are architects pioneering its use such as Cave Urban whose research and work includes bamboo structures at the annual Bondi exhibition, Sculpture by the Sea.

Sculpture by the Sea exhibit by Cave Urban

In our world of depleting resources bamboo is a sustainable, fast growing, strong alternative to timber. With a tensile strength superior to mild steel and a weight-to-strength ratio surpassing that of graphite, bamboo is the strongest growing woody plant on earth with one of the widest ranging habitats. With time, the applicability and use of bamboo will be adopted by the industry realising its true potential... and when it does there will be an irreversible shift in the construction industry.

Kontum Indochine Restaurant by Vo Trong Nghia Architects

Bamboo Courtyard Teahouse by Sun Wei Architect

Roc Von Restaurant by Vo Trong Nghia Architects

Further info:

Bamboo University is run by the Kul Kul Farm in Bali, Indonesia in collaboration with Ibuku: www.kulkulfarmbali.com

Cave Urban is a collective that explores the intersection between art and architecture through the use of bamboo: www.caveurban.com

IBUKU create buildings that are a testament to the power of bamboo and the possibilities of sustainable architecture: www.ibuku.com

Building with Bamboo by Gernot Minke is a detailed manual for bamboo constructions and presents a broad selection of built examples: www.bookdepository.com

Review: Deerubbin Architecture Conference

This last weekend I was fortunate enough to attend the Deerubbin Architecture Conference on Milson Island in the Hawkesbury River, a weekend of good architecture and good people all together. There were no VIP events that speakers were whisked away to following their presentations, everyone mingles around drinking coffee and enjoying lunch with one another - and this was no lightweight conference either, three packed days of presentations from both internationally and locally acclaimed architects including Peter Stutchbury, Richard Leplastrier and Gabriel Poole. Also in attendance were architecture legends Glenn Murcutt and Juhani Pallasmaa.

This last weekend I was fortunate enough to attend the Deerubbin Architecture Conference, organised by the Architecture Foundation Australia on Milson Island in the Hawkesbury River. The conference takes its name from the aboriginal name for the river, meaning 'deep and wide water', and this attribution to the lands original custodians set a tone for the whole conference, a tone of respect and engagement between those speaking at the conference and those attending it. There were no VIP events that speakers were whisked away to following their presentations, everyone mingles around drinking coffee and enjoying lunch with one another - and this was no lightweight conference either, three packed days of presentations from both internationally and locally acclaimed architects including Peter Stutchbury, Richard Leplastrier and Gabriel Poole. Also in attendance were architecture legends Glenn Murcutt and Juhani Pallasmaa. To top off this first class line up, the conference was held on the beautiful Milson Island, within an architectural gem designed by Sydney Architects Allen Jack+Cottier Architects. As we enjoyed the speakers presentations we also enjoyed the view through the full length low level window to the trees and bush outside as walkers passed by and the occasional brush turkey scratched among the leaves looking for food.

To commence the conference we were treated to a traditional aboriginal welcoming ceremony by Uncle Max Dulumunmun Harrison, an Aboriginal Elder of the Yuin People whose gentle nature and charismatic sense of humour gave a light hearted but deeply respectful start to the conference.

The first speaker of the conference was Lene Tranberg of Lundgaard + Tranberg, a leading architect from Denmark. Lene showed a brief presentation of a handful of her practices projects in Denmark, addressing the theme of the conference, 'hot and cool'. The image below is of the Tietgen Dormitory near the Danish capital, Copenhagen. The building is a circular form with a generous central courtyard where students gather. The interaction between public spaces and the division of private, public and semi-public have been thoughtfully arranged resulting in both a beautiful and functional space for students to live.

After an all too brief exploration of the island the next morning, Saturdays presentations were kicked off by Professor Brit Andresen, the first female recipient of the RAIA Gold Medal. Brit gave an overview of her education and the events and projects that led to her moving to Australia. Brit talked us through a series of beautiful residential projects and their relationship with the environment and climate of tropical Queensland, including the house shown in the image below, Mooloomba House.

Following Brits talk was Chris Major, one half of the Sydney practice Major + Welsh. Chris opened with the practices first commission and followed with a series of projects including a number of award winning projects. The practice was only established in 2004 but since then has been involved in a wide range of innovative projects and has established a reputation for delivering responsive and engaging architecture in the public and private realm. The image below is a commercial redevelopment of the former Rocks Police Station, a delicate adaptive reuse project for this historic police station.

The next talk was from Antoine Perrau, of the French Island in the Indian Ocean, Réunion, an island where the brutal trade winds and heat demand a responsive approach to architecture that Antoine has been perfecting with his practice over the years. Antione not only presented a cross section of his projects on the island but also explained the varying site conditions based on each projects location on the island. To take things one step further, Antoine then broke down the strategies in place to deal with the harsh climatic conditions and how these strategies result in comfortable conditions without the need for air conditioning or other means of active cooling - the product of this is not only sustainable architecture, but an architecture that is 'of place', suited specifically to its conditions as well as its use. The image below is of a Primary School in Saint André.

After lunch, our next speaker was Julie Stout of Mitchell + Stout from New Zealand. Julie took us on a journey of hers and her partners travels on their sailing boat throughout the pacific, showing some of her sketches of the local architecture she encountered on those islands. As the story continued with their return to New Zealand and the projects they began to work on, the influence of the cultures that had encountered in their travels was immediately apparent. Julies buildings expressed a beautiful tactility and used materials that were designed to age and take on a beautiful patina. She also got a some laughs from the audience when she told the story of her husbands aversion to maintaining the plants that grow across the façade of their house, referring to it as 'going to mow the bloody house'. The image below is of an amazing bedroom Julie created at the Waiheke Island House.

The final speaker for the night was one that many had been looking forward to - Gabriel Poole, a Queensland legend, whom hasn't given a public talk in over 20 years. Now in his 80's, Gabriel is well known for his enlightened house designs and innovative use of materials. Along with other distinguished accolades he has received the Robin Boyd Award and the RAIA Gold Medal for his lifetime contribution to Australian Architecture. After a series of presentations of works across his long career, Gabriel concluded with a heartfelt attribution to his wife Lizzy for the support, inspiration and collaboration she has provided him over the years. The crowd gave Gabriel a well-deserved standing ovation to which he said "I'm too old for this - you're all going to make me cry." The image below is of a project from 1996, Lake Weyba House.

On Saturday night we were treated to a BBQ dinner, live blues band and some drinks with speakers, fellow architects, students and all else attending the conference. The next morning was kicked off with a presentation by Ingerid Helsing Almaas, Editor-in-chief of Arkitektur N, the Norwegian Review of Architecture magazine. Ingerid game us a snapshot of Norways beginnings and linked this to how the countries architecture has had to respond to harsh conditions as well as dispelling a few myths about Norwegian architecture. In addition to analysing the challenges that Norwegian architects face in a climate of such extreme cold she also showed a series of beautiful projects from the National Tourist Route project which has seen a number of unique small projects dotted across Norway to provide facilities, viewing platforms and visitors centres along the eighteen tourist routes. To close her talk, Ingerid proposed a challenge to Norweigan architects current approach to keep nature at arms length, something to be viewed as a way of dealing with the harsh conditions, speculating on the possibility of engaging with the environment as a means to deal with the conditions just as the architecture of the tropics often does. The image below is of a work Ingerid showed by Norweigan legend Sverre Fehn.

The final presentation of the conference was presented by architecture greats, Richard Leplastrier and Peter Stutchbury. In the theme of the conference, 'hot and cool', the pair proposed to cut a section through the architectural styles ranging from the Inuit Igloos in the Northern Hemisphere, all the way down to wind battered Southern coast of Tasmania and New Zealand - no small feat in a one hour presentation, yet Richard and Peter (or Rick and Stutch as they are affectionately referred to by those attending) pulled it off flawlessl - A presentation that was informative and evocative, showing both works of traditional architecture such as the Hakka walled villages in China through to their own personal projects such as the Wall House by Peter. The pair seamlessly presented their talk, bouncing ideas off one another as they moved through the slides. An invigorating presentation that was the perfect culmination to a weekend of good people and good architecture all together.

Many thanks to the Architecture Foundation Australia for organising such a great conference and a special mention to Lindsay Johnston, convener, 'creative director' and MC for the weekend. I'll leave you with the words that Gabriel Poole left us with at the end of his presentation:

If a house is built only for shelter,

It is not truly a house for ones soul,

As much as we need a place where we can cook and sleep,

We need a place where our souls can play.

(Ancient Japanese Poem)

Choosing the right Hardwood

Timber is a wonderfully familiar material that delights our senses, whether touch, sight, smell or sound. It is one of the most fundamental materials with which we make things and is inseparably connected to the history of mankind.

I have prepared this post to assist those seeking to find an Australian hardwood that is right for them and right for the application...

Tin Shed House by Ironbark Architecture featuring spotted gum battens

Timber is a wonderfully familiar material that delights our senses, whether touch, sight, smell or sound. It is one of the most fundamental materials with which we make things and is inseparably connected to the history of mankind.

I have prepared this post to assist those seeking to find an Australian hardwood that is right for them and right for the application. It is not an exhaustive list but presents a brief overview of nine Australian hardwood species.

BLACKBUTT

The common name “Blackbutt” comes from the regular appearance of a blackened base on the trunk of the tree, caused from fires. Blackbutt primarily grows in the coastal regions of southern NSW all the way up to south east QLD. It has a quick growth rate and is easily regenerated, making it a popular species to grow in plantations and a readily available timber on the east coast of Australia. The heartwood colour ranges from a yellowish brown to light brown, with a fairly straight grain and even texture with gum veins sometimes present. Blackbutt has a very good fire rating and is one of the 7 timber species found suitable for bushfire prone areas. A hard, strong and durable timber, Blackbutt is increasingly popular choice for flooring and decking in Australia, with Parliament House in Canberra showcasing the spectacular beauty of Blackbutt by using it for its flooring.

PROS

Readily Available in Decking

Highly durable and hard

1 of 7 hardwoods recommended for bushfire prone areas

PROPERTIES

Name

Durability

Density

BAL Rating

Termite Resistant

Lyctid Borer Susceptible

Tannin Leach

Origin

CONS

Tendency to surface checking and splitting

High tannin content – may leech when wet

Mostly supplied in random lengths

Eucalyptus Pilularis

Class 1

880 kg/m³

12.5 / 19 / 29

Yes

No

Moderate

NSW / QLD

IRONBARK

The common name “Ironbark” comes from the trees tendency to not shed its bark annually like many other eucalyptus, resulting in an accumulation of dead bark. This layer of bark protects the living tissue inside the tree from fires, and with a silvery-grey colour looks quite similar to iron metal and hence the name. Ironbark is usually seen growing, in both native forests and plantations, in the western area of NSW up to southern QLD, with some trees growing in northern VIC. Ironbark has a very high natural resistance to rot due to chemistry of the tree which helps fight off fungus. The heartwood has a deep red colour which is a great contrast to the pale yellow sapwood. Both heartwood and sapwood are often seen together in decking boards. Ironbark timber has an interlocked grain with a fine texture. Ironbarks popularity is ever increasing with more and more homes using the timber for decks, landscaping and cladding due to its high durability and fire resistance.

PROS

High rot and termite resistance

Very high durability, hardness and density

Widely available

Used for over 200 years in heavy construction

Little tannin leach

1 of 7 hardwoods recommended for bushfire prone areas

PROPERTIES

Name

Durability

Density

BAL Rating

Termite Resistant

Lyctid Borer Susceptible

Tannin Leach

Origin

CONS

Hard to work, can blunt tools quickly

Boards need to be pre-drilled

Expensive

Short oil life of decking due to density

Mostly supplied in random lengths

Red ironbark is Lyctid borer susceptible

Eucalyptus Sideroxylon (red)

Eucalyptus Paniculata (grey)

Class 1

1090 kg/m³

12.5 / 19 / 29 (red)

12.5 / 19 (grey)

Yes

Yes (red)

No (grey)

Little

VIC / NSW / QLD

JARRAH

The common name “jarrah” is also the aboriginal word for both the tree and timber. Jarrah timber reflects the tones of the southwest WA landscape from where it comes from, with very deep red colours seen in the heartwood. Jarrah has an attractive grain with some incidence of wavy or interlocking grain occurring, and a moderately coarse texture. Jarrah timber is quite similar to red ironbark in which it is a very dense and hard timber, both sharing the deep red colours. Jarrah is also naturally weather, rot, termite and marine borer resistant making it a highly durable timber for outdoor purposes, however the sapwood of the timber is Lyctid borer susceptible, so the sapwood present in decking may sometimes be treated. Jarrah availability is somewhat limited due to the slow growth of the trees and the fact the timber can only be sourced from old growth forest and native forest regrowth in WA. It’s for this reason jarrah decking should be sourced from recycled means when obtainable.

Jarrah Decking Example (dry)

Jarrah Decking Example (wet)

PROS

Highly durable and dense

Rot, termite and weather resistant

Retains natural colour for longer due to close grain

Little tannin leach

PROPERTIES

Name

Durability

Density

BAL Rating

Termite Resistant

Lyctid Borer Susceptible

Tannin Leach

Origin

CONS

Limited availability

Sourced from old growth forests

Expensive

Requires pre-drilling

Mostly supplied in random lengths

Lyctid borer susceptible

Eucalyptus Marginata

Class 2

820 kg/m³

12.5 / 19

Yes

Yes

Little

WA

KARRI

The “Karri” tree is Australia’s and one the world’s tallest hardwoods growing up to 70m in height, allowing for longer lengths of timber being able to be milled, knot-free. Karri heartwood is a beautiful hue of reddish-brown, being slightly lighter in colour then jarrah. Also like Jarrah, the Karri grows in the wetter regions of southwest WA and also cultivated internationally. Availability of Karri is slightly greater then Jarrah, but still limited due to the most of the timber now in conservation reserves and regrowth forest. Karri timber has an interlocked, sometimes straight grain, with a course texture. Karri is moderately durable, with a reputation of being termite-prone, however not nearly as prone as untreated pine.

Karri Decking Example

PROS

Longer lengths of timber available, knot-free

Cheaper than other hardwoods, like jarrah and ironbark

High strength

PROPERTIES

Name

Durability

Density

BAL Rating

Termite Resistant

Lyctid Borer Susceptible

Tannin Leach

Origin

CONS

Termite-prone

Somewhat limited in availability

Pre-drilling required

Poor reputation to holding paint and impregnation of preservatives

Mostly supplied in random lengths

Not as durable as other Australian hardwoods

Eucalyptus Diversicolour

Class 2

900 kg/m³

12.5 / 19

No

No

Little

WA

REDGUM

“Forest Redgum” is a very distinctive timber in Australia, with almost everyone having come in contact with or heard of it. It has had an important part in Australia’s history being used in a range of applications from the very first settlers up until today. The timber, as the name suggests, has a striking red colour which ranges from a light to deep-dark red. Redgum has a fine and even texture with the grain being interlocked and often producing a ripple or fiddleback figure, which makes for a very attractive feature in decking boards. Redgum is a very versatile, dense and durable timber that grows in a wide range of areas from south-east VIC all the way east up until southern Papua New Guinea. Even though most of the timber has been locked away in protected forests, Redgum is still widely available on the East coast of Australia due to the broad area Redgum is found growing in. Some companies sell a mix of both Redgum and Red Ironbark (very similar timbers) often marketed as forest reds.

Redgum Decking Example

PROS

Highly durable and hard

Termite resistant

Readily available

PROPERTIES

Name

Durability

Density

BAL Rating

Termite Resistant

Lyctid Borer Susceptible

Tannin Leach

Origin

CONS

Some gum veins present in timber

Mostly supplied in random lengths

Eucalyptus Tereticornis

Class 1

960 kg/m³

12.5 / 19

Yes

No

Little

VIC / NSW / QLD / PNG

SILVERTOP ASH

“Silvertop ash”, or sometimes named “coast ash” due to its occurrence to grow along the coast of the south-eastern areas of Australia, is a moderately durable and relatively light hardwood compared to other eucalyptus like spotted gum and ironbark. The timber has a medium texture with a straight grain, also showing noticeable growth rings. The timber also often comes with natural features including gum veins and ambrosia, giving the timber a unique look. Silvertop ash is readily available through the eastern states of Australia, with its main source being from native forests, with some trees being grown internationally, in New Zealand plantations. Silvertop Ash is very popular amongst architects where being left to “silver off” in applications such as cladding and retains a smooth even finish with little to no tannin leach on surfaces below.

PROS

Less expensive hardwood decking

1 of 7 hardwoods recommended for bushfire prone areas

No tannin leach

Widely available

Easy to work, excellent for nailing and screwing

Accepts coatings and preservatives well

Can be supplied in set lengths

PROPERTIES

Name

Durability

Density

BAL Rating

Termite Resistant

Lyctid Borer Susceptible

Tannin Leach

Origin

CONS

Termite-prone

Relatively prone to surface checking and splitting

Not as durable as other Australian hardwoods

Light to medium feature present in timber

Eucalyptus Sieberi

Class 2

850 kg/m³

12.5 / 19 / 29

No

No

Little

TAS / VIC / NSW

SPOTTED GUM

The common name “spotted gum” is used for four different highly durable and dense Corymbias (spotted gum was previously classified as a eucalypt, until it was changed in the mid-1990’s) that grow along the east coast of Australia, but more commonly refers to the species, Corymbia Maculata. They get their common name from the pale, smooth bark in the trees trunks that have shed in small patches leaving the tree with a “spotted” appearance. The different species commonly referred to as spotted gum only differ in appearance, not in durability or other properties. The heartwood of spotted gum ranges from a light brown to a dark reddish-brown. The sapwood of the timber is Lyctid borer susceptible, so is commonly treated to help keep the timber free of the bugs. The timber often comes with an attractive wavy grain with coarse and uneven texture; it also is noted as having a “greasy” feel when you run your hand over machined products. Spotted gum is grown throughout the eastern part of Australia and in some parts of WA and SA in both native forests and plantations. Spotted gum is currently QLD’s largest harvested native hardwood by volume, meaning that spotted gum is widely available throughout Australia, with quantities also being exported internationally.

PROS

Readily available throughout Australia

1 of 7 hardwoods recommended for bushfire prone areas

Highly durable, dense, and hard

Widely available

Little tannin leach

Sustainably sourced

PROPERTIES

Name

Durability

Density

BAL Rating

Termite Resistant

Lyctid Borer Susceptible

Tannin Leach

Origin

CONS

Expensive

Requires pre-drilling

Mostly supplied in random lengths

Lyctid borer susceptible

Corymbia Maculata

Class 1

990 kg/m³

12.5 / 19

Yes

Yes

Moderate

VIC / NSW / QLD

TALLOWWOOD

The timber commonly known as “Tallowwood” owes its name to the greasy feel of the wood once it has been cut or machined, due to its naturally oily composition. The decking should be left to weather slightly (2-3 weeks) before giving it a sanding, slight wash with a deck cleaning product and oil. It is a highly durable and dense timber, which is highly resistant to decay due to its ability to withstand damp and wet conditions relatively well; however the softwood of the timber is Lyctid borers susceptible, so any sapwood present in the decking boards maybe have to be treated to help keep them free of the bugs. The heartwood colour ranges from a pale to dark yellowish brown, with a moderately coarse texture and interlocked grain. Availability of tallowwood is fairly common, with most of the resource being sourced from native forests on coastal regions between southern Newcastle, NSW and Maryborough, QLD. Because of it’s oily nature, it is a good choice for decking around pool areas.

Tin Shed House by Ironbark Architecture featuring Tallowwood decking

PROS

Termite Resistant

Very high durability and density

Good resistance to surface checking

High resistance to decay

Performs well in wet environments – good for pool areas

PROPERTIES

Name

Durability

Density

BAL Rating

Termite Resistant

Lyctid Borer Susceptible

Tannin Leach

Origin

CONS

Mostly available in random lengths

High tannin / oil content

Pre-drilling required

Lyctid borer susceptible

Eucalyptus Microcorys

Class 1

990 kg/m³

12.5 / 19

Yes

Yes

Little to moderate

NSW / QLD

YELLOW STRINGYBARK

“Yellow Stringybark” is the common name for three different eucalypt species, which all have a thick, fibrous bark that were once used as early European settlers for roof and wall thatching. The heartwood of the timber comes up a light yellowish-brown colour, very similar to that of tallowwood and Silvertop Ash. It has a medium to fine texture, often seen with an interlocked grain, also showing some features as gum veins and ambrosia. Yellow Stringybark mainly grows in native forests and some plantations on the coastal and tableland areas of southern NSW and eastern VIC, making it readily available in south-eastern states.

Yellow Stringybark Decking Example

Yellow Stringybark Decking Example

PROS

Readily available in south-east areas

Being grown in sustainable plantations

Termite resistant

Can be supplied in engineered lengths

Excellent result from oil based finishes

PROPERTIES

Name

Durability

Density

BAL Rating

Termite Resistant

Lyctid Borer Susceptible

Tannin Leach

Origin

CONS

Gum veins sometimes present

Eucalyptus Muelleriana

Class 2

880 kg/m³

12.5 / 19

Yes

No

Little

VIC / NSW

FINISHING TIMBER - SEALING AND OILING

A discussion about timber would be incomplete without saying something about timber finishing, which is essential not only for aesthetic appeal but also for protecting the wood from environmental factors. Different finishing methods are employed depending on whether the timber is intended for indoor or outdoor use. The different products available are extensive, but let's look at three popular products that we use in our projects.

Water-Based Urethane

Water-based urethane finishes offer a durable and versatile solution for sealing indoor timber surfaces. These finishes provide excellent protection against moisture, stains, and scratches while also enhancing the natural beauty of the wood. Architects often opt for water-based urethane finishes due to their low odor, fast drying time, and easy cleanup. Additionally, they are available in various sheen levels, allowing for customization to suit different design preferences. Unlike oil based urethane finishes, water based products will not turn yellow over time from exposure to UV. This is why the cypress floors you’ll see in 1950s to 1980s homes will appear orange, when in reality cypress has a beautiful tan brown colour.

Hardwax Oil

Hardwax oil is a popular choice among architects for finishing indoor timber surfaces. This natural oil-based product penetrates deeply into the wood, providing long-lasting protection and enhancing the timber's natural characteristics. Hardwax oil creates a durable yet breathable finish that is resistant to water, heat, and household chemicals. One of the key advantages of hardwax oil is its ease of application and maintenance, making it ideal for both residential and commercial projects. Hardwax finishes are not quite as durable as a urethane finish, but have the advantage that they can be spot repaired without the need to sand back and refinish a large area as a urethane finish would need.

Cutek Extreme CD50

When it comes to finishing outdoor timber, Cutek is the only product that I specify. A proven wood protection system, Cutek penetrates deep into the timber, forming a barrier against moisture, UV radiation, and fungal decay. It is designed to fade naturally over time, without flaking or peeling. To maintain some colour in the timber (although it will still lighten) there are Colourtone’s that can be added prior to application.

This oil-based solution allows the wood to breathe while providing long-term protection against the harsh Australian climate. Applying Cutek has a “compounding” effect, so requires two to three coats on installation and a follow up coat within the next 6-12 months. After these initial coats, the timber can be allowed to “silver-off” and the product will continue to protect the timber even though the surface looses it’s original colour. Followingf that, weathered surfaces can typically be left up to 4-5 years without recoating, potentially longer in protected settings. The maintenance of timber with Cutek Extreme CD50 does not require stripping or sanding the coat. Simply clean the surface and reapply the oil every two to seven years. This applies even if the weathering off approach is desired for a project. The maintenance intervals and rate of fading will vary depending on the wood species, the specific situation, design, and the degree of exposure to the elements.

There is one significant draw back to Cutek that is a virtue of the nature of the product. During cold, wet and cloudy weather, the product will have a significantly difficult time drying and soaking into the timber. Application of Cutek is most effective during warm, sunny weather, and coats should be applied with multiple thinner coats, rather than less but thicker coats.

Cutek Extreme CD50. Image courtesy Mortlock Timber.

The Essentials of Good Design

Good design is neither magical nor mysterious - it is the inevitable result of consistently applying the correct basic fundamentals. It was one of the great pioneers of modern architecture, Meis van der Rohe, who said “I don’t want to be interesting. I want to be good”.

I believe that if you focus on getting the fundamentals of a design correct, everything else will fall into place in time. This is by no means an exhaustive list as there are endless factors to be considered (...and I also don't want to put myself out of work!!) but the following will highlight some of the key factors to consider...

Can Lis by Jørn Utzon/ Image Source: www.kunst.dk

Good design is neither magical nor mysterious - it is the inevitable result of consistently applying the correct basic fundamentals. It was one of the great pioneers of modern architecture, Meis van der Rohe, who said “I don’t want to be interesting. I want to be good”.

I believe that if you focus on getting the fundamentals of a design correct, everything else will fall into place in time. This is by no means an exhaustive list as there are endless factors to be considered (...and I also don't want to put myself out of work!!) but the following will highlight some of the key factors to consider;

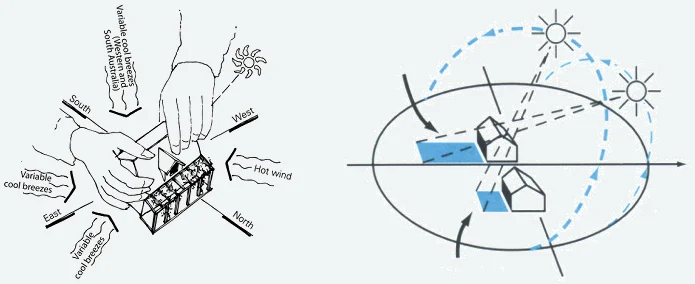

Orientation

My biggest criticism of 'off-the-shelf' or project homes is their lack of response to orientation. Anyone can appreciate the need to orient a design towards a view of the ocean but good orientation goes beyond that... A well oriented design can benefit from shaded indoor and outdoor living areas when the weather is hot, and provide sunny indoor and outdoor areas when the weather is cold. Whilst large areas of glass may facilitate keeping a house warm in Winter, too much glass to the West may cause excessive heat gain in the afternoons of warmer months. Good orientation can also facilitate cross ventilation, which I will come back to. Because every site is different and of a different shape and size good design needs to consider all the factors that will result in the correct orientation - two identical houses in the same location will respond very differently if they face different directions.

Image Source: www.yourhome.gov.au

Passive Design

To attempt to explain the benefits of passive design in one paragraph would be futile - at its core passive design is an approach to design that seeks to use the surrounding environment to its benefit rather than fighting against the elements. A house of good passive design doesn't require air-conditioning to run year round in order to keep its occupants comfortable, in fact it is entirely possible for a house to be designed on any site without needing air conditioning to keep the spaces comfortable - human beings are incredibly adaptable and our bodies can regulate comfort within a given range of temperature and humidity. Entire books and manuals have been written on the different ways to utilise passive design in architecture. A few examples;

1. The heat stack effect uses the natural tendency for hot air to rise and by allowing heat to escape through high level windows. The rising warm air reduces the pressure in the base of the building, drawing cold air in through either open doors, windows, or other openings.

2. Thermal mass uses the natural qualities of dense materials like concrete or bricks to delay heat flow into a building during the day and storing the heat to release the warmth into the building at night. Although not a substitute for insulation, correct use of thermal mass can moderate internal temperatures by averaging day/night extremes which can increase comfort and decrease energy bills.

3. Insulation acts as a barrier to heat flow and keeps unwanted heat out of your home in the hotter months whilst preventing heat loss during cooler months, however it is essential that insulation is used in conjunction with good design. For example if insulation is installed but windows have not been correctly shaded, built up heat can be kept in by the insulation creating an 'oven' effect.

Image source: Albert, Righter and Tittmann Architects

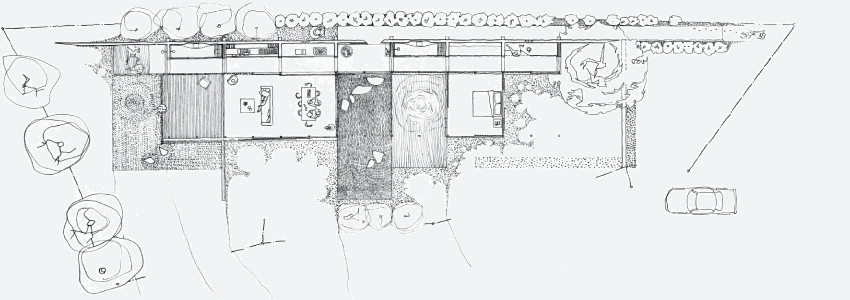

Layout & Circulation

A house should have a distinct character to its layout, it may be an elongated plan to maximise natural light throughout the house, or it may comprise of multiple pavilions to provide separation between a parents realm and a children's realm, brought together by a common living realm, or it may be a courtyard style plan to provide multiple outdoor living spaces and provide an inward outlook on a site that may not have any significant views. Whatever the style of the layout, it should always have good circulation, houses with narrow corridors and dog-legs will eventually feel like living in a maze. If a house has good circulation it will feel like it has 'flow' but circulation extends beyond just the corridors... it begins with the approach to the building, the view experienced as you walk through the front door and where the bedrooms are located within the building. All the best buildings you have ever experienced had good circulation.

Floor plan of Wall House by Peter Stutchbury

Prospect & Refuge

The evolutionary perspective explains that humans are not as well equipped as animals. We don’t have fur to protect us against climate changes. That is why we need a shelter against weather changes like rain, wind and cold. We also need a shelter to protect us from these animals, because we don’t have claws or a shield to defend ourselves. The instinctual need for prospect and refuge is still hard wired into us today. A good example of prospect and refuge is in a house designed by Jørn Utzon (architect of the Sydney Opera House) called Can Lis on the Spanish Island of Majorca. The house provides sweeping views of rugged hills with untamed nature and the ocean beyond (prospect), whilst the deeper recesses of the house offer vary degrees of light and dark giving a sense of protection (refuge).

Prospect and Refuge: Szachownica Cave in Poland/ Can Feliz by Jørn Utzon

Ventilation

Air motion significantly affects body heat transfer by convection and evaporation. Air movement results from free (natural) and forced convection as well as from the occupants’ bodily movements. The faster the motion, the greater the rate of heat flow by both convection and evaporation. In summer air movement can be increased with the use of ceiling fans or by cross ventilation. Cross ventilation requires well-designed openings (windows, doors and vents) and unrestricted breeze paths. A well ventilated building will also improve the air quality within a dwelling, although it is easy to cool or heat a building with air conditioning, the quality of air is inherently lower than that of a cross ventilated design. Caution is required, however, to ensure that a building can be sealed well in cooler months as only a small velocity of air movement is required in cool weather to create discomfort. High quality windows that seal well are always recommended.

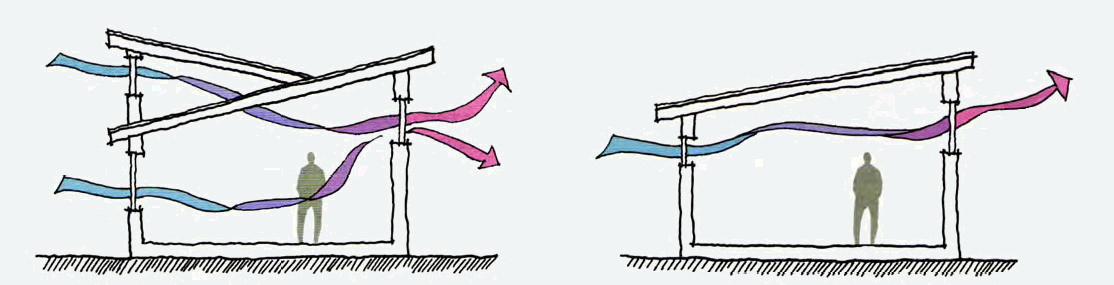

Image Source: The Green Studio Handbook, Alison G. Kwok

Materials

Consideration should be given to the materials from which your house will be constructed with. Materials should be suitable to the location, locally available, recyclable to some degree and integrated with the design. Some materials are tried and tested such as masonry and concrete and others have utilised the latest technologies in their development. The range of available choices is not short, but don't be afraid of doing something different to the 'norm'. Using lightweight materials can reduce the environmental impact of transportation energy as well as reduce labour costs. Consider using materials in their natural state (ie. don't require additional coatings such as paint or render), the result can be a lower maintenance house that also visually expresses how it has been crafted. The materials used and type of construction can also significantly affect the passive design performance of the design.

Angophora House by Richard Leplastrier

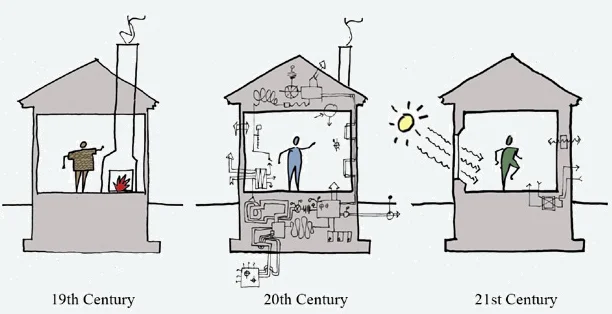

Energy Use

The average household's energy use is responsible for over seven tonnes of greenhouse gas emissions. These emissions can be significantly reduced through use of renewable energy, more efficient appliances and energy conservation measures. There are endless ways in which you can cut the energy demand of your household - some are as simply as providing a well ventilated fridge space so that it can run efficiently, or replacing your lights with compact fluorescent or LED lamps. More involved measures include minimising your homes heat gain and heat loss (see passive design above), increasing natural lighting to minimise requirements for artificial lighting or installing renewable energy sources such as photovoltaic panels or a wind turbine. A big consumer of energy in the home is your hot water system, there are a range of low energy devices on the market now including instantaneous gas hot water units, solar hot water units and heat pumps (heat pumps can also be coupled with a photovoltaic system and/or a hydronic underfloor heating system).

Wind Generator / Photovoltaic Panels / Gas Instantaneous Hot Water Unit

Water Use

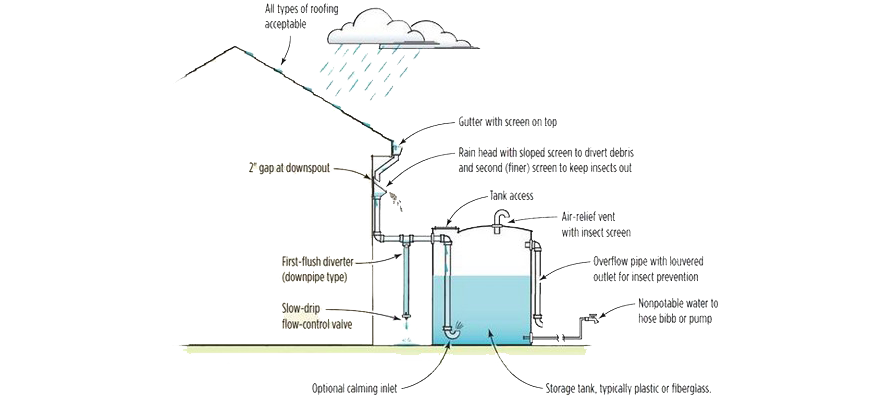

One of our most important resources on this planet is water, without it life would not be possible. What many fail to acknowledge is how many people on this planet are deprived of access to clean drinking water; you may be amazed at just how many cities around the world it would be unsafe for you to drink the water from the tap! For this reason, and many others, we should all consider ways in which we can make better use of this precious commodity. As with energy use, the first step in conservation is to reduce demand; fit water efficient showerheads, fix leaking taps, install a rainwater tank, etc.

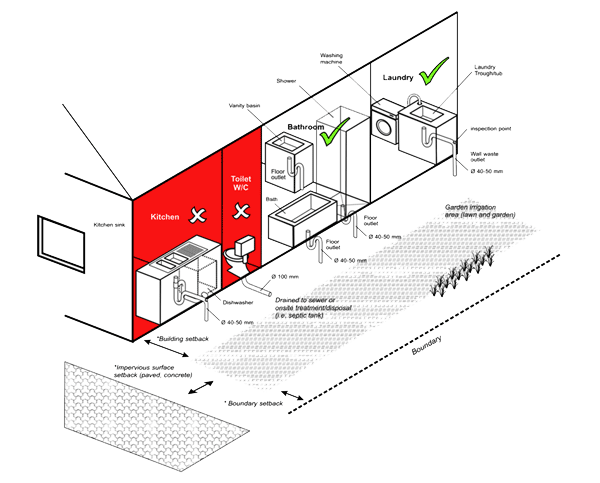

There are three main types of household water - Potable (drinkable), greywater (used water. ie. basins, showers, etc.) and blackwater (toilet, kitchen sink, dishwasher, etc.). I have written three posts to explain each of the types of household water types as well as ways that they can be reduced, reused or recycled.

Water Talk - Part I - Rainwater

Water Talk Part II - Greywater

Water Tank Part III - Blackwater

A typical rain water harvesting setup / Image Source: http://pixshark.com/)

To find out more visit the Australian Governments guide to environmentally sustainable homes at http://www.yourhome.gov.au/

or, read Nick Hollo's book 'Warm House Cool House' which can be bought online.

or, visit Michael Mobbs 'Sustainable House' tours in Chippendale. To book for his regular tours visit the website here. To learn more about my services as a local architect, get in touch with me through my contact form today. I work across projects in the Sutherland Shire, through to the Northern Beaches across Manly, Pittwater, Avalon, to Palm Beach.

Construction in Paradise

Most architects, if fact, most people would like to find themselves taking part in a project to help underprivileged societies at least once in their lifetime, so when I was invited by another local architect to join them in taking part in a project run by a small Australian charity, ‘Books Over The Sea’, to build a new library for the school children of Vacalea Primary School in Fiji, I jumped at the opportunity...

Most architects, if fact, most people would like to find themselves taking part in a project to help underprivileged societies at least once in their lifetime, so when I was invited by another local architect to join them in taking part in a project run by a small Australian charity, ‘Books Over The Sea’, to build a new library for the school children of Vacalea Primary School in Fiji, I jumped at the opportunity.

The project was created by Andrew Verus who is a senior firefighter in the NSW Fire Brigade. When he was 25, along with friends, they cashed in their savings and bought a small piece of land on the island of Kadavu in Fiji and built a traditional styled accommodation for small groups of backpackers and scuba divers. Throughout the seven years that Andrew ran the accommodation, a lasting friendship was built with the people of the nearby village of Vacalea. Now, more than a decade after the accommodation has been sold to new owners, Andrew continues to support the village and its people. Following discussions with the people of the village about the needs of the village, the idea to build a school library was born.

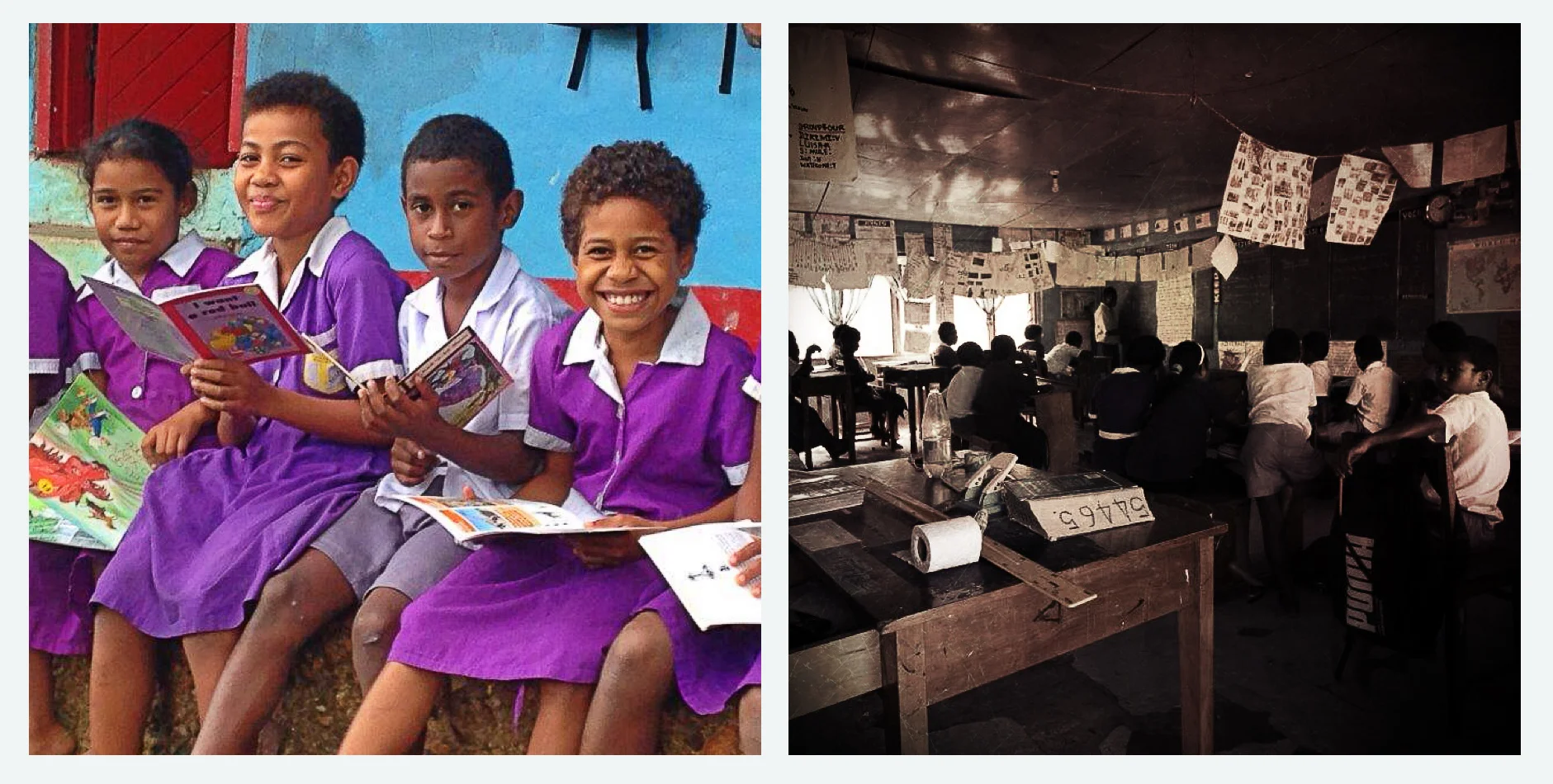

Vacalea (pronounced va-tha-lay-a) is a small village of less than 100 people and is located on the Eastern side of Kadavu Island in Fiji. Despite being the fourth largest island in Fiji, Kadavu is quite remote and one of the most under developed parts of the country. The school has 80 students with three simple classrooms and very limited resources. In remote villages like these, families combine their very modest finances to build schools so their children don't have to walk five to six hours to attend one of the few Fijian Government-built schools on the island. The government does however provide the teachers as well as the syllabus.

Whilst Andrew went about making plans to realise his project, he enlisted the help of Sydney architects, Couvaras Architects, who provided plans to be submitted to the Fijian authorities for approval as well as plans for construction of the library. The library was designed as a simple 6 x 8m structure that could be built with local materials using construction methods that the local Fijians were familiar with. The plans were provided by Couvaras Architects at no charge and whilst Andrew has applied for financial aid from the Australian High Commission, he has funded all the work done to date from his own pocket.

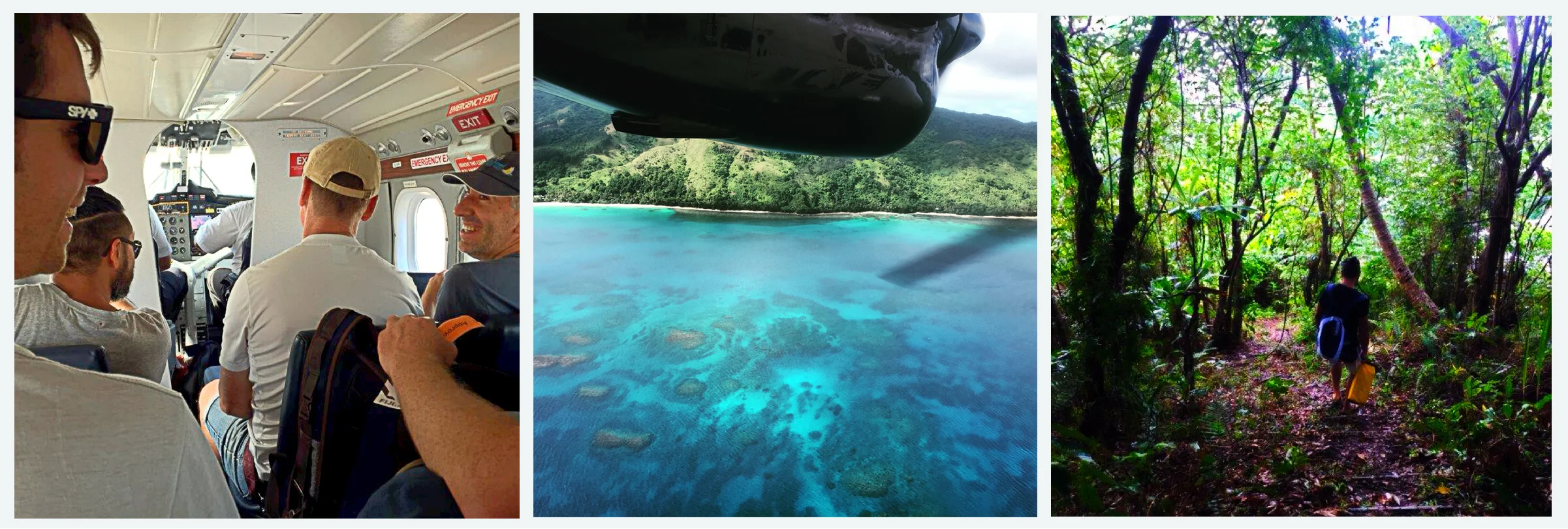

We set out from Sydney on the first of June taking a flight to Nadi, the main island in Fiji, then the next day a flight to Kadavu Island on Fiji Airways smallest aircraft, a plane so small that in order to be given the safety briefing the captain simply turned around and spoke to all 12 passengers before we barrelled down the runway in this tin can with wings.

From the airport we rode across the small town in the back of a ute to the water’s edge where we were picked up by two longboats to take us to the village. Our captains possessed an uncanny knowledge of the waters as they navigated the beautiful reefs, with waters of constantly changing hues of aqua, blues and greens as we passed countless islands with nothing to see but forests, ocean and endless sky.

The morning we arrived at Vacalea village to begin construction of the libraries foundations we were greeted by a few local villagers and some curious children who all took turns to shake our hands as we stepped ashore. The school is located just outside the village and comprises of a block of three classrooms, a toilet block, a dormitory for the children from other villages who go home just on weekends, a teachers quarters and a rugby field (what Fijian school would be complete without one?). Most of the buildings were timber framed structures lined with corrugated steel on the walls and roof, except for the classrooms, which were located in a concrete block building. Despite all being quite simple structures, most were painted bright colours of blue or green and had a certain charm about them, set amongst their lush setting of long grass and palm trees.

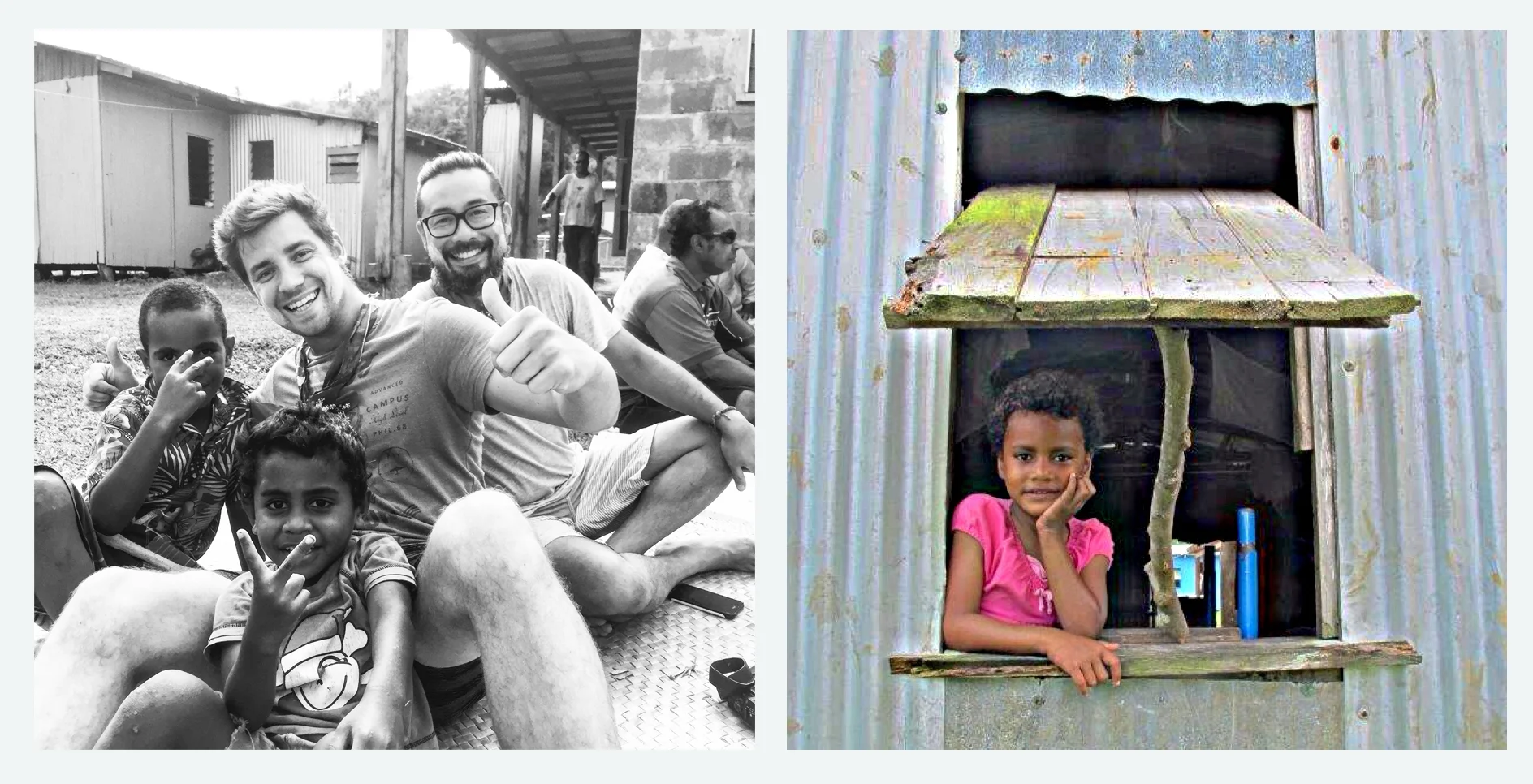

As we commenced making plans as to where the building would be located, a few cheeky children strayed from their classrooms to have a look at the “kaivalagi” - a Fijian word meaning someone from the land of the foreigners. As the location of the building was confirmed by a few sticks stuck into the ground, a workforce of about 30 or so boys and men from the village turned up - these men had taken time away from their farms or other duties to lend us a hand in building the library, an unexpected, but welcome, surprise. As a few of us went about setting up string lines to mark out the location of each foundation post, the rest of us struck up conversation with the Fijians who had come to help, exchanging names and asking one another questions, “Where in Australia are you from?”, “Do you play rugby?”, “What do you farm?”.

When the call was made to start digging we all set to work furiously digging a hole for each of the foundation posts to be located in. We later learned that Fijians quite like to work in large groups like this (we also learned that the Fijians could dig holes a whole lot quicker and better than we could!) and the whole thing is treated as a bit of fun: telling jokes, singing songs, stirring each other up and if anything needs to be passed along a line, like buckets of concrete, well that’s just a good opportunity to get a bit of rugby practice in.

At the end of each day’s work we all sit down in a group together and a few key men of the village express their thanks to us for offering our time and resources to provide their children with something that most remote schools don't have: a dedicated library. After the thanks and some prayer, the men begin to sing songs, each man joining in the harmony where his voice best fits. Sitting amongst them all, I realise this is quite a special moment. As the singing continues some women arrive from the village with necklaces made of fresh flowers for each of us as a traditional way of honouring guests. Next some musical instruments arrive as well as the kava (kava is a Fijian specialty, drunk at all kinds of occasions and leaves your mind relaxed but tastes distinctly like muddy water). The kava is served in quite a ceremonial fashion, first to the chief, then to the guests and then to everyone else. As the party gets into full swing, we are invited to dance and serve the kava to the women. The singing, dancing and laughing continues until we leave, when we are again thanked, as every member of the village takes the time to shake each of our hands.

Thanks to the extra help we complete the foundations of the building in a little over two days, bringing the first phase of the construction process to a close. We have set out the building's location, dug 36 holes and set in concrete a timber footing post in each. On the 12th of August six fire fighters from Kogarah Fire Station will travel to Vacalea to build the floor, walls and roof. Once the building is complete, Andrew will ship to the village donated books, shelving, desks and a computer to transform the simple structure into Vacalea Public School's first ever library.

If you would like to make a donation to the construction costs or donate books for the library you can contact Andrew Verus on 0422 849 541 or email supportus@booksoverthesea.org.au You can also follow Books Over The Sea on Facebook www.facebook.com/booksoverthesea

More photos to come as construction of the library progresses…

Water Talk Part III

Blackwater is a polite way of describing sewerage and includes not only sewerage from toilets but also the water from kitchen sinks and dishwashers due to the presence of pathogens and grease. The idea of recycling blackwater may be something that repels many people at first, but read a little further and you may see that this crazy idea isn't as crazy as you might first think...

Blackwater is a polite way of describing sewerage and includes not only sewerage from toilets but also the water from kitchen sinks and dishwashers due to the presence of pathogens and grease. The idea of recycling blackwater may be something that repels many people at first, but read a little further and you may see that this crazy idea isn't as crazy as you might first think...

Although it may be simpler and cheaper to flush away your sewerage problems the benefits of blackwater recycling are worth the effort for those willing to take their sustainable contribution to the next level. Blackwater contains pathogens that make it hazardous to humans in its raw form but it is also very high in nutrients making it suitable to irrigate gardens following treatment and reduces the individual impact upon the environment.

There are several ways in which blackwater can be treated, some using chemicals to disinfect the effluent, however some use no chemicals and very little energy by duplicating the natural process of decay by which organic matter is broken down. Systems such as the Biolytix BioPod use worms and other organisms to efficiently convert household sewage into garden irrigation water.

Inside the tank of a Biolytix Biopod is a layered filter bed, engineered to separate the solids from the liquid wastewater and to house the organisms that quickly convert separated solids to a stable humic layer. The organisms, including worms, ensure the filter bed is naturally aerated, so that there is none of the smell associated with septic tanks and mechanically aerated wastewater systems. Near the bottom of the tank is a geofabric layer, which removes fine solids down to 80 micron size and is continually biologically cleansed. Below this is the purified water ready to be pumped to the garden. The system is self-maintaining so only requires servicing by a technician once annually.[1]

Recycling blackwater is likely not to be everyone’s cup of tea, however those who are committed to reducing their impact on the environment sometimes means getting ones hands dirty (don’t take that literally!) and put aside the stigmas associated with blackwater.